Dealing With Difficult People: Why Conflict Feels Personal and How to Handle It

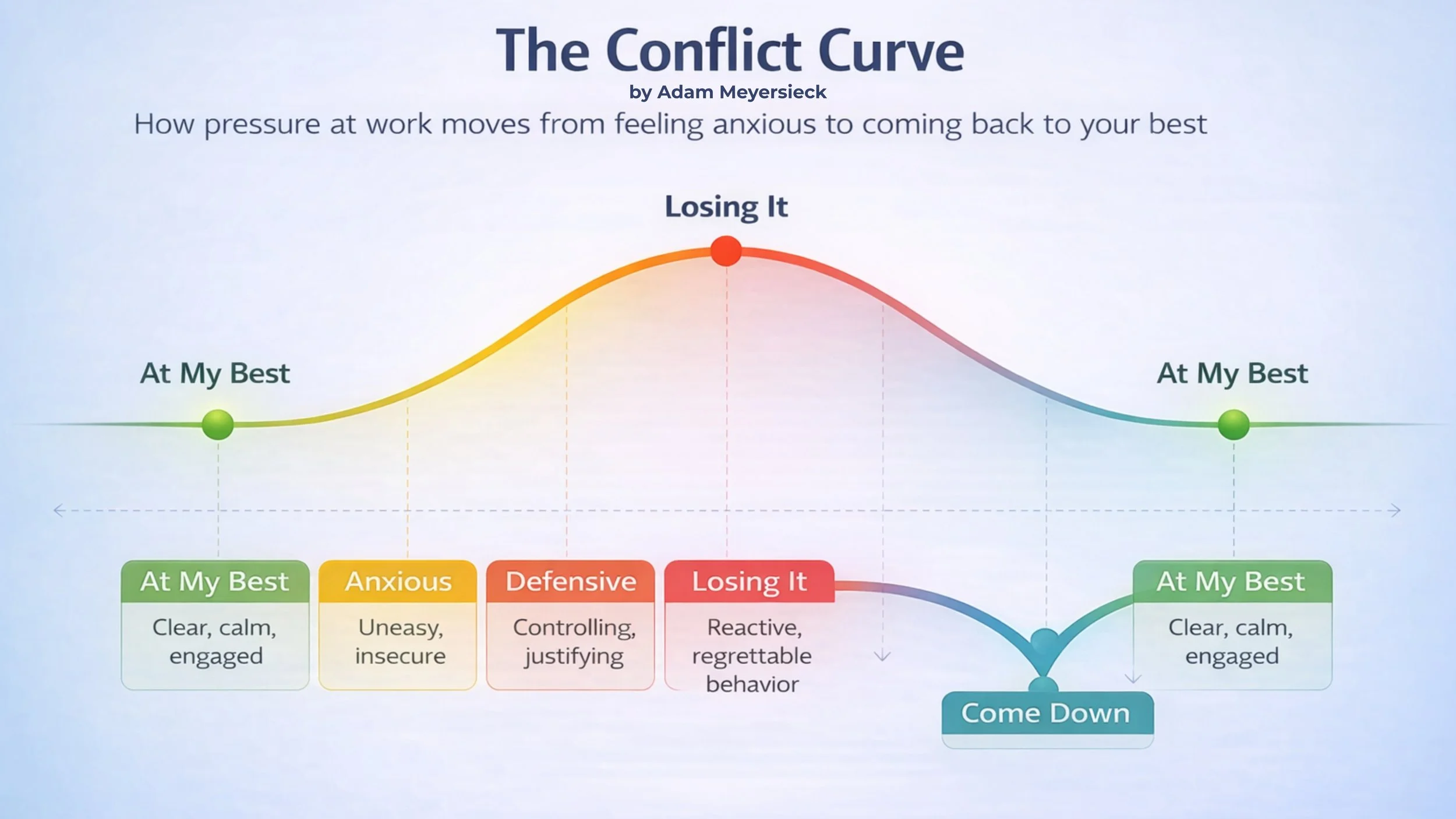

The Conflict Curve

If you’ve spent any time at work, you’ve worked with someone you’d quietly describe as “difficult.” Sometimes that person is a colleague. Sometimes it’s a manager. And sometimes, if we’re being honest, it’s us. Conflict at work has a way of feeling personal even when everyone involved would say they’re focused on the task. That’s because conflict doesn’t begin with behavior. It begins internally, long before words or tone give it away.

One useful way to understand this is through what I call The Conflict Curve. The Conflict Curve describes how pressure at work gradually shifts from internal tension to outward behavior.

This isn’t a tool for diagnosing people or labeling personalities. It’s a way to notice what happens in you when things get tense, and to recognize the moments where you still have choices about how you respond.

Let's dive in!

At Your Best

The Conflict Curve doesn’t start with anxiety. It starts with understanding what baseline looks like for you when things are going well.

“At your best” isn’t about being perfect, endlessly patient, or calm in every situation. It’s about how you work, think, and relate to others when you feel clear, steady, and engaged. This is the version of you that collaborates well, handles feedback without bracing, and stays flexible when things change.

When you’re at your best, work tends to flow. You communicate more openly. You listen without rehearsing your response. You make decisions without rushing or over-explaining. Effort is still there, but friction is lower.

This stage matters because it gives you a reference point. Without it, it’s hard to recognize when you’ve started to drift up the Conflict Curve. With it, early signals become easier to spot.

It’s worth asking:

What does “at my best” actually look like for me at work?

How do I communicate when I feel grounded and clear?

What behaviors tell me I’m regulated and engaged?

What conditions make this state more likely?

Anxious

The first upward movement on the Conflict Curve often shows up as anxiety. Many people picture anxiety as nervousness or feeling stuck. In reality, anxiety in this model looks different for everyone. It’s the moment when something feels off but hasn’t yet turned into conflict.

That might be your reaction to an unclear expectation, a sudden change in direction, a meeting where you feel unprepared, or a person whose communication style consistently puts you on edge.

When anxiety shows up, people tend to act in predictable ways. Some talk more. Some withdraw. Some over-prepare or mentally rehearse arguments that haven’t happened yet. None of these responses are wrong. They’re signals that your nervous system is paying attention. The question is whether you notice those signals or move past them.

I often ask people to start here: What does anxiety look like or sound like for me?

What do you do when you feel anxious? What might you typically do or say?

Protective Positioning

When anxiety isn’t addressed, the Conflict Curve often moves into Protective Positioning. This is Fight or Flight time. It's the stage many people would traditionally call defensiveness, but “protective positioning” better captures what’s happening. You’re not trying to be difficult. You’re trying to protect your credibility, your role, or your sense of control.

Interactions start to feel sharper here. Feedback lands harder. Questions sound like challenges. You may find yourself justifying, interrupting, or controlling the narrative instead of listening. Protective positioning can feel necessary in the moment, but it narrows your options.

At this stage, it’s easy to focus on what the other person is doing wrong. It’s harder, and far more useful, to notice what’s happening internally. Slowing down, asking clarifying questions, or naming what you need can interrupt the curve here. These moves don’t require perfection. They require awareness.

What does this look like or sound like for you? What do you do when you feel protective? What might you typically do or say?

Losing It

Further along the Conflict Curve is the point most people recognize immediately: losing it. At work, this doesn’t have to look dramatic. It might be a sarcastic comment, a sharp email, a public correction, or a decision made too quickly out of frustration. It can also show up as shutting down, disengaging, or going quiet in ways that affect the team.

By the time you reach this point, your nervous system is largely in charge. Logic takes a back seat, and tone does most of the communicating. This is why earlier awareness matters so much. Once you’re here, the goal isn’t to win the interaction. It’s to limit the damage.

The Aftermath

Eventually, everyone comes back down the Conflict Curve. This phase is often overlooked, but it may be the most important. After tension passes, energy drops below baseline. You see the mess. You notice the impact. You may feel embarrassment, regret, or a strong desire to move on as quickly as possible.

People respond differently here. Some replay the moment repeatedly. Some avoid it entirely. Others pretend nothing happened. How you handle The Aftermath says a great deal about your leadership.

Repair doesn’t require a long explanation or an emotional conversation. It requires ownership. A brief acknowledgment, a reset, or a clarification can restore trust far more effectively than pretending the moment didn’t matter.

Neurodiversity and the Curve

Neurodiversity adds another layer to this conversation. Different nervous systems move along the Conflict Curve differently. Some escalate quickly and de-escalate quickly. Others hold tension quietly until it surfaces later. Some live close to anxiety or protective positioning more often than they’d like.

Sensory load, processing speed, communication styles, and past experiences all influence how conflict feels and how it’s expressed. Understanding the Conflict Curve doesn’t remove these differences. It helps leaders and teams work with them more intentionally.

Begin With You

Working with difficult people starts with understanding how conflict works inside you. That awareness isn’t about self-criticism. It’s about self-leadership. The more familiar you are with your own Conflict Curve—how you act, respond, and react—the more capacity you have to stay steady when work gets hard.

And in most organizations, that steadiness is one of the most valuable contributions a leader can make.